A few years ago, when I embarked on my doctoral research in engineering, little did I know that I would have to do experiments on human cadavers. I have always been interested in engineering and never thought that I would have to deal with biology of any kind at any time in my research career.

However, a personal crisis that unfolded at that time had a bearing on my research as well. My father was diagnosed with a blockage in the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). He had to undergo neurosurgery involving spinal needle puncture procedure. Post-surgery, he developed unbearable and prolonged headaches. Pained by my father’s agony, I began to explore the completely alien field of neurosurgery, especially spinal needle punctures.

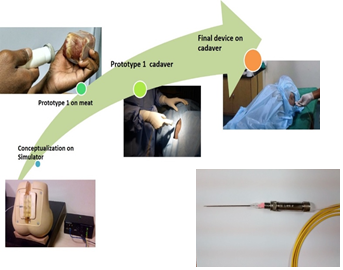

I approached many doctors and surgeons who specialized in spinal and neurological surgeries. Several sessions of discussion with one particular orthopaedic surgeon helped my understanding of the spinal needle puncture procedure. I also learned the reasons for its severe side effects. A slight over-puncture or a wrong puncture can lead to side effects, including severe headaches. This led to begin my work on the development of a technology for estimating the needle position to have precise insertion and it became one of my doctoral research topics. I soon developed novel prototypes of assistive sensing devices. Initial trials were performed on lab-based lumbar puncture simulator models used to train medical students. To get the feel of actual tissue puncture, trials on fresh meat pieces too were carried out. After several trials, the surgeon suggested real-time validation of the device on human cadavers. This was something I was completely unprepared for.

I approached many doctors and surgeons who specialized in spinal and neurological surgeries. Several sessions of discussion with one particular orthopaedic surgeon helped my understanding of the spinal needle puncture procedure. I also learned the reasons for its severe side effects. A slight over-puncture or a wrong puncture can lead to side effects, including severe headaches. This led to begin my work on the development of a technology for estimating the needle position to have precise insertion and it became one of my doctoral research topics. I soon developed novel prototypes of assistive sensing devices. Initial trials were performed on lab-based lumbar puncture simulator models used to train medical students. To get the feel of actual tissue puncture, trials on fresh meat pieces too were carried out. After several trials, the surgeon suggested real-time validation of the device on human cadavers. This was something I was completely unprepared for.

Although nervous, I mentally prepared myself for the cadaveric experiments. The cadaveric investigations were scheduled in the Surgical Skills Training & Research Laboratory at Ramaiah Advanced Learning Centre, Bengaluru. This institute with world class cadaveric research facility is adjoining the Indian Institute of Science (where I was enrolled for my PhD).

On the appointed day, my colleague and I accompanied the surgeon, and although I thought I was prepared for this, my first encounter with a dead human body was terrifying. With the embalming stench, I thought I would faint. In a daze, I watched as the surgeon punctured the lower spinal region of the cadaver with spinal needle mounted on the new device. My device worked. When the surgeon confirmed it, I felt both overwhelmed and a bit frightful given the situation I was in. The surgeon perhaps realized the condition, and he did his best to keep me engaged by interacting continuously with us.

In that first visit, I was only a passive discussant as my eyes were on the cadaver. I was curious to know who the dead person was and why he was there. Soon, I was out of the facility, and after some more discussions, the surgeon offered lunch. My hunger had vanished, and I rushed home to wash up and relax. The whiff of the stench did not leave my senses. It remained for days, and I would wake up to the smell of the embalming fluid. For the next six months, I visited the facility regularly for further experimentations and data collection. Although, experiments with cadavers became a regular activity, I never could get over the anxiety. During one of the visits, the cadaver had been prepared and positioned for the needle puncture, but the prototype did not work. I was hit by a sense of guilt and got to work immediately to rectify the error and proceeded to experiment.

In that first visit, I was only a passive discussant as my eyes were on the cadaver. I was curious to know who the dead person was and why he was there. Soon, I was out of the facility, and after some more discussions, the surgeon offered lunch. My hunger had vanished, and I rushed home to wash up and relax. The whiff of the stench did not leave my senses. It remained for days, and I would wake up to the smell of the embalming fluid. For the next six months, I visited the facility regularly for further experimentations and data collection. Although, experiments with cadavers became a regular activity, I never could get over the anxiety. During one of the visits, the cadaver had been prepared and positioned for the needle puncture, but the prototype did not work. I was hit by a sense of guilt and got to work immediately to rectify the error and proceeded to experiment.

Eventually, the experiments were successful. I completed my doctoral research and developed a medical assistive device in the interdisciplinary field of biomedical sensing. For developing the device for spinal needle positioning, I received the CSIR Young Scientist Award (Physical Science)-2019 from Dr Harsh Vardhan, then Hon’ble Union Minister and Vice-President CSIR.

The technology may not have helped my father, but I developed some technical expertise, and more importantly gained some precious life lessons. During my visits to the cadaver facility, I had seen groups of medical students surrounding cadavers for learning and practice as their regular activity. My first-hand experience of working on and realizing the significance of human cadavers will remain unforgettable.

Dr Shikha,

Scientist, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India.

Pensioners Corner

Pensioners Corner Screen Reader Access

Screen Reader Access Skip to main content

Skip to main content